Science Center for Marine Fisheries (SCeMFIS)

June 09, 2020

Keeping your clam chowder chock full of tasty Arctica islandica clams (i.e., quahogs), the type of clams used in clam chowder and maintaining healthy stocks of these bottom-living sea creatures —is of critical interest to the U.S. shellfish industry. To do this requires a sound understanding of the ocean quahog life cycle. However, how long these clams live and how fast they reproduce is somewhat mysterious because telling the age of an Arctica cannot be done just by looking at it and details about its reproduction are unclear.

To get these answers, members of the shellfish industry asked the Science Center for Marine Fisheries (SCeMFiS)—an Industry-University Cooperative Research Center funded by the National Science Foundation—to help uncover the unknowns in quahog life cycles.

One of the goals of this IUCRC is to help clam fisheries avoid overfishing while keeping their yearly quotas robust. Harvesting Arctica is a $34-million a year industry and requires consideration of environmental, economic, and ecological concerns. Researchers at SCEMFIS developed a way to use imaging and software technology to uncover how quickly these clams reproduce and grow large enough to replace quahogs that are harvested from the seabed.

How Old is a Quahog?

The Arctica clam is long-lived. In U.S. waters, using techniques developed by SCeMFiS, the oldest ocean quahog was found to be around 240 years old, says Eric Powell, director of SCEMFIS. To put that in perspective, he adds, “that animal was born before the Revolutionary War.”

Only large Arctica are harvested. Most clams of that size are at least 60 years old, but many can be much older. The distribution of ages in the population is important because a sustainable fishery depends upon consistent recruitment (i.e., reproduction and growth) balancing the numbers removed by the fishery. For a long-lived species, understanding recruitment is critical because rebuilding an overfished stock can require a long period of time. Knowing the distribution of ages in the population reveals these all-important recruitment dynamics.

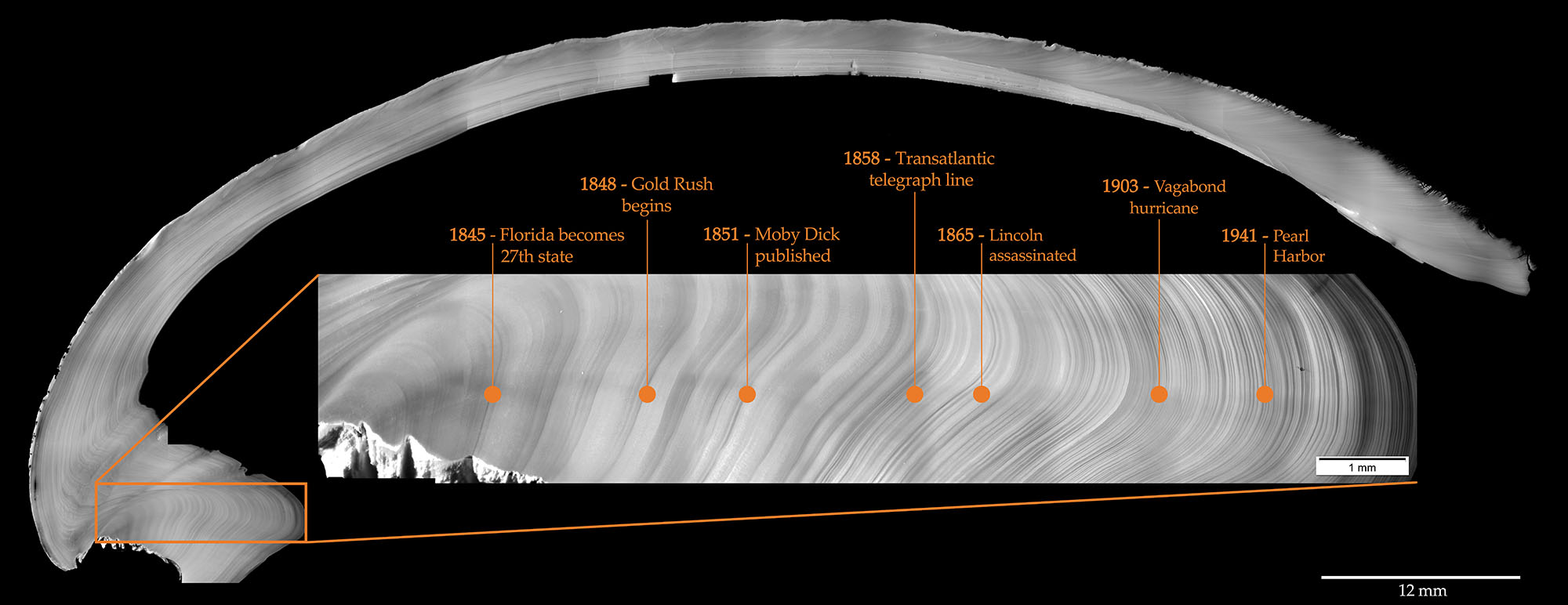

As Arctica grows, the clam produces a ring of shell each year. Similar to the way a tree grows tree rings. As in a tree, the number of layers in a quahog shell equals the age of the clam. Counting quahog rings isn’t a new idea, and there was already a technique for aging each clam. The problem was it was tedious and slow. “A good technician might be able to do one [clam] a day,” said Powell. But to fully understand the range of ages and growth rates at a fishing site, a team needs to collect and count 700 to 1,000 quahogs. Aging that many animals could take years!

To speed up the process, SCEMFIS researchers used a new method to age each quahog. They first took high-resolution photographs of the cut shells, tiling the images together. The images are highly detailed, spanning 20,000 by 8,000 pixels, which clearly highlight the growth lines of the Arctica. Each image is then run through a software program that allows technicians to annotate and measure the growth history of the clams.

“We've made a big step forward in coming up with a method that's much more efficient at allowing us to age a large number of animals, which is absolutely critical to answer the fishery’s questions of how much harvesting can be done while maintaining a sustainable stock,” says Powell.

Growth in Mid-Atlantic Quahogs

Although their research is ongoing, the SCEMFIS team has made some important discoveries in mid-Atlantic Arctica clams. Powell says one of the first thing they discovered is that the growth rates are speeding up over time.