Center for Identification Technology Research (CITeR)

August 03, 2020

Information, Communication and Computing

Making a payment can be as easy as hovering a smartphone or a smart credit card over a contactless console. A similar touchless technology is on the horizon for fingerprint identification.

In high-traffic areas, like airport security lines, customs, and border crossings, contactless fingerprint ID could reduce wait times and limit the spread of germs. It could give law enforcement officers the flexibility of capturing fingerprints in the field with a mobile phone camera rather than relying on more cumbersome, expensive fingerprinting equipment.

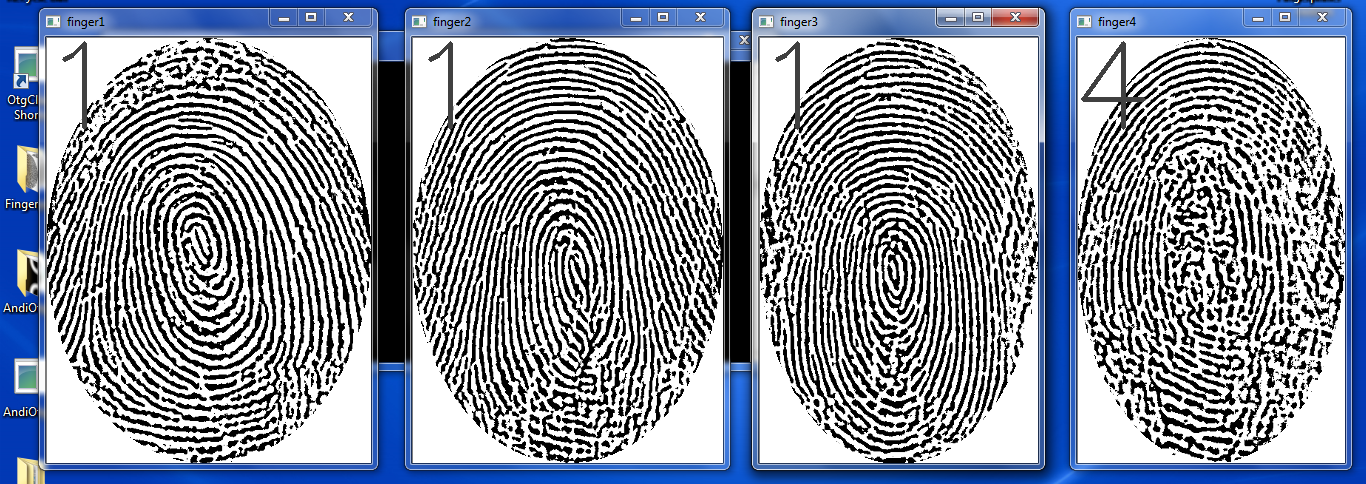

But making this technology a reality requires overcoming a significant hurdle. Existing fingerprints stored in global databases have been made by touch, which slightly deforms the tiny lines in the print. As a result, touchless prints don’t exactly match those collected by touch, creating a big identification gap.

Jeremy Dawson, associate professor of computer science and electrical engineering at West Virginia University and his teammates, led by Nasser Nasrabadi, a professor of computer science and electrical engineering at West Virginia University, are working on technology to make contactless fingerprint ID more reliable. By collaborating with dozens of affiliates from the security sector who belong to the Center for Identification Technology Research (CITeR) — an Industry-University Cooperative Research Center (IUCRC) funded by the National Science Foundation to improve identity science and biometric recognition — the researchers have developed an algorithm that bridges the gap between touch and touchless fingerprint technology.

The advance will help a range of government organizations and private companies, from the U.S. Department of Defense to smartphone makers like Apple and Samsung, and will help transition to a faster, more flexible, and hygienic fingerprint security method.

Training the Algorithm

To create a system that’s able to match the two different kinds of prints, the researchers developed a deep-learning algorithm that learns from what it’s shown and then uses that knowledge on new information. They first fed the algorithm tens of thousands of known legacy fingerprint images taken with a touch-based sensor as well as tens of thousands of images of fingerprints taken with contactless technology. Next, they asked the algorithm to look for subtle differences between the two types of fingerprints. The researcher repeated this learning phase tens of thousands of times.

After training the algorithm, the researchers began feeding it sets of fingerprints it hadn’t seen before and asking it to find matches. In Dawson’s most recent experiments, the algorithm was 99% accurate at finding a match on this relatively small dataset. Dawson and his team want to push accuracy to 99.999%, but that’s not easy and it will depend on gathering a dataset of tens of millions of individuals.

“We’re training a machine to see the differences in these prints. It then knows that these two different samples collected in different ways belong to the same person,” Dawson noted.

Acquiring a large number of fingerprints for training and testing the algorithms was one of the biggest challenges, says Dawson. Because of privacy issues, fingerprint databases from law enforcement offices, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, are not available for research. Since 2008, Dawson has been building a database of tens of thousands of touch-based and touchless fingerprints from students, staff, and residents of the surrounding community who have signed consent forms to participate in human subjects’ research. No record is tied to a name to maintain the person’s privacy, and the fingerprints are never entered into any civil or criminal database.

The team submitted a patent application for the technology in Spring 2020 and is actively searching for an industry partner to develop a software package that can be licensed.